New York Marble Cemetery

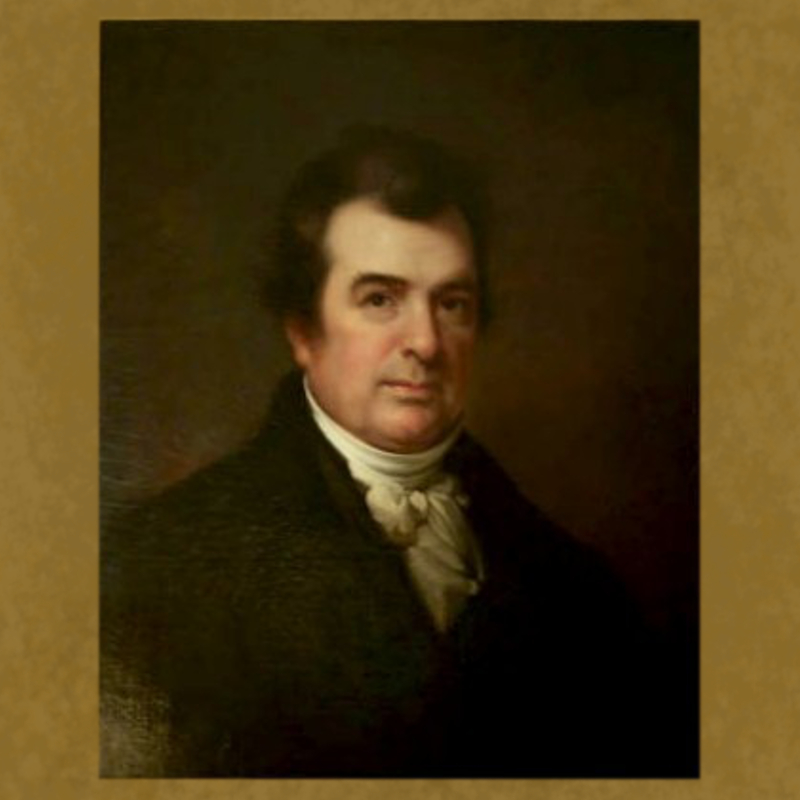

David Hosack by Rembrandt Peale, 1826

Courtesy Columbia University College of Physicians & Surgeons

David Hosack, 1769-1835

by Penelope Rowlands

Born in Manhattan in 1769, David Hosack [pronounced Huzz-ick] lived, both geographically and socially, at the very center of New York. He was a friend and confidante of some of the more distinguished citizens of the early Republic, including General Alexander Hamilton, among numerous others; as the attending physician at the General’s duel with Aaron Burr in 1804, he cared for Hamilton in his last hours on earth.

Educated at Princeton, Columbia, and the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school, Hosack taught at two institutions, both of which he’d helped to found: Columbia University’s College of Physicians & Surgeons and the short-lived Rutgers Medical School (which opened in New York City in 1826 and closed a few years later). Hosack was famously charismatic — students flocked to his lectures for entertainment as well as for what they could learn.

As a doctor, Hosack is best remembered for facing down New York City’s fiercely politicized medical establishment when yellow fever closed in on New York in the early 1800s; the treatment he advocated, in the face of ridicule from his colleagues, saved countless lives. He also had many medical innovations to his credit: At the age of 26, he became the first doctor to tie off the femoral artery in the treatment of aneurism; he was also an early advocate of the use of the stethoscope and the first to operate on hydroceles by injection. In addition, Hosack was a founder of several New York institutions that survive to this day, including Bellevue Hospital and The New York Historical Society.

The doctor is particularly known for having founded the Elgin Botanic Garden on a hilly, heavily wooded, twenty-acre patch of land that would later become Rockefeller Center; the first botanical garden in the United States at a time when pharmacology was plant-based, the Elgin was a center of learning for medical students and doctors alike.

By the time Hosack died, in 1835, he was one of the city’s most famous citizens. His imprimatur was enormous – and had a direct effect on the fate of the New York Marble Cemetery. When Hosack bought a vault there a few years before his demise, other early New Yorkers flocked to do the same and, before too long, the cemetery had became the place to be buried in Manhattan.

Written by: Penelope Rowlands